PEG ratio

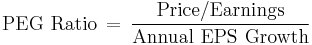

The PEG ratio (Price/Earnings To Growth ratio) is a valuation metric for determining the relative trade-off between the price of a stock, the earnings generated per share (EPS), and the company's expected growth.

In general, the P/E ratio is higher for a company with a higher growth rate. Thus using just the P/E ratio would make high-growth companies appear overvalued relative to others. It is assumed that by dividing the P/E ratio by the earnings growth rate, the resulting ratio is better for comparing companies with different growth rates.[1]

The PEG ratio is considered to be a convenient approximation. It was popularized by Peter Lynch, who wrote in his 1989 book One Up on Wall Street that "The P/E ratio of any company that's fairly priced will equal its growth rate", i.e., a fairly valued company will have its PEG equal to 1.

Contents |

Basic formula

The growth rate is expressed as a percentage above 100%, and should use real growth only, to correct for inflation. E.g. if a company is growing at 30% a year, and has a P/E of 30, it would have a PEG of 1.

A lower ratio is "better" (cheaper) and a higher ratio is "worse" (expensive).

The P/E ratio used in the calculation may be projected or trailing, and the annual growth rate may be the expected growth rate for the next year or the next five years.

Examples:

- Yahoo! Finance uses 5-year expected growth rate and an averaged P/E for calculating PEG (PEG for IBM is 1.26 on Aug 9, 2008 [1]).

- The NASDAQ web-site uses the forecast growth rate (based on the consensus of professional analysts) and forecast earnings over the next 12 months. (PEG for IBM is 1.148 on Aug 9, 2008 [2]).

PEG as an indicator

PEG is a widely employed indicator of a stock's possible true value. Similar to PE ratios, a lower PEG means that the stock is undervalued more. It is favoured by many over the price/earnings ratio because it also accounts for growth.

The PEG ratio of 1 is sometimes said to represent a fair trade-off between the values of cost and the values of growth, indicating that a stock is reasonably valued given the expected growth. A crude analysis suggests that companies with PEG values between 0 to 1 may provide higher returns.[2] The PEG Ratio can also be a negative number, for example, when earnings are expected to decline.This may be a bad signal, but not necessarily so. Under many circumstances a company will not grow earnings while its free cash flow improves substantially. Here, as in other cases, analyzing the components of PEG becomes paramount to a successful investment strategy.

The PEG ratio is commonly used and provided by various sources of financial and stock information. The PEG ratio, despite its wide use, is only a rule of thumb and has no accepted underlying mathematical basis. Its specific mathematical deficiency is explained here.

The PEG ratio's validity at extremes in particular (when used, for example, with low-growth companies) is highly questionable. It is generally only applied to so-called growth companies (those growing earnings significantly faster than the market).

When the PEG is quoted in public sources it may not be clear whether the earnings used in calculating the PEG is the past year's EPS or the expected future year's EPS; it is considered preferable to use the expected future growth rate.

It also appears that unrealistically high future growth rates (often as much as 5 years out, reduced to an annual rate) are sometimes used. The key is that management's expectations of future growth rates can be set arbitrarily high; this is a self-serving ploy where the objectives are to keep themselves in office and to make the stock artificially attractive to investors. A prospective investor would probably be wise to check out the reasonableness of the future growth rate by checking to see exactly how much the most recent quarter's earnings have grown, as a percentage, over the same quarter one year ago. Dividing this number into the future P/E ratio can give a decidedly different and perhaps a more realistic PEG ratio.

Advantages

Investors may prefer the PEG ratio because it explicitly puts a value on the expected growth in earnings of a company. The PEG ratio can offer a suggestion of whether a company's high P/E ratio reflects an excessively high stock price or is a reflection of promising growth prospects for the company.

Disadvantages

The PEG ratio is less appropriate for measuring companies without high growth. Large, well-established companies, for instance, may offer dependable dividend income, but little opportunity for growth.

A company's growth rate is an estimate. It is subject to the limitations of projecting future events. Future growth of a company can change due to any number of factors: market conditions, expansion setbacks, and hype of investors. Also, the convention that "PEG=1" is appropriate is somewhat arbitrary and considered a rule-of-thumb metric.

The simplicity and convenience of calculating PEG leaves out several important variables. First, the absolute company growth rate used in the PEG does not account for the overall growth rate of the economy, and hence an investor must compare a stock's PEG to average PEG's across its industry and the entire economy to get any accurate sense of how competitive a stock is for investment. A low (attractive) PEG in times of high growth in the entire economy may not be particularly impressive when compared to other stocks, and vice versa for high PEG's in periods of slow growth or recession.

In addition, company growth rates that are much higher than the economy's growth rate are unstable and vulnerable to any problems the company may face that would prevent it from keeping its current rate. Therefore, a higher-PEG stock with a steady, sustainable growth rate (compared to the economy's growth) can often be a more attractive investment than a low-PEG stock that may happen to just be on a short-term growth "streak". A sustained higher-than-economy growth rate over the years usually indicates a highly profitable company, but can also indicate a scam, especially if the growth is a flat percentage no matter how the rest of the economy fluctuates (as was the case for several years for returns in Bernie Madoff's Ponzi scheme).

Finally, the volatility of highly speculative and risky stocks, which have low price/earnings ratios due to their very low price, is also not corrected for in PEG calculations. These stocks may have low PEG's due to a very low short-term (~1 year) PE ratio (e.g. 100% growth rate from $1 to $2 /stock) that does not indicate any guarantee of maintaining future growth or even solvency.

References

- ^ Easton, Peter D. (January 2002), Does The Peg Ratio Rank Stocks According To The Market's Expected Rate Of Return On Equity Capital?, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=301837

- ^ Khattab, Joseph (April 6, 2006), How Useful Is the PEG Ratio?, The Motley Fool, http://www.fool.com/investing/value/2006/04/06/how-useful-is-the-peg-ratio.aspx, retrieved November 21, 2010